This subject guide was prepared by Graham Willett and Kathy Sport for a Melbourne Engagement Grant project

- Julian Phillips

- Terry Stokes case

- Student organisations

- Victorian Women's Liberation and Lesbian Feminist Archives

- Related records in other University of Melbourne collections

For most of Australian history, homosexuality** was a vilified, marginalised and, for men, criminalised state of being. (Sexual relations between women have never been illegal in the British legal system, though it has been reported that offensive behaviour charges were used against public displays of affection). And yet, as decades of research have started to reveal, women and men with same-sex desires find ways to live and love, to celebrate, to support each other. The sexual history of Australia is much richer than we might have thought.

The University of Melbourne has not always lived up to its commitment as a place of freedom of thought, unfettered exploration and fearless learning, however, close examination of archival records reveals the ways in which the inner-city campus has played a role in understanding the diversity of Australian life.

This was especially true beginning in the 1960s as society started to break the shackles of conformity – of thought and of behaviour – which had been entrenched for such a long time. New thinking was on the march, at the University, as much as anywhere else.

Amongst the myriad of issues that were under challenge, older ideas of homosexuality as a sin, a crime, and a pathological condition were questioned. On campus, new liberalism found the place and the space to express itself in the student newspaper Farrago and in Debating Society gatherings. The first public meetings in Melbourne to discuss homosexuality took place at the University of Melbourne with a Debating Society discussion in 1964 and a public meeting in 1970. In 1969, when the lesbian organisation Daughters of Bilitis wanted to reach out, they also chose the campus as the place to do so.

By the early 1970s homosexual activists – now calling themselves gay and lesbian – were campaigning openly, proudly, confidently demanding that society change – laws, attitudes, professional and public opinion. Many (but not all) academics and students supported the new politics of sexuality. There were opposing views and many difficulties in trying to change the laws.

Funded by the Melbourne Engagement Grant Scheme, Graham Willett and Kathy Sport have examined the University of Melbourne Archives for evidence of the University’s contribution to gay law reform and to the broader discourse.

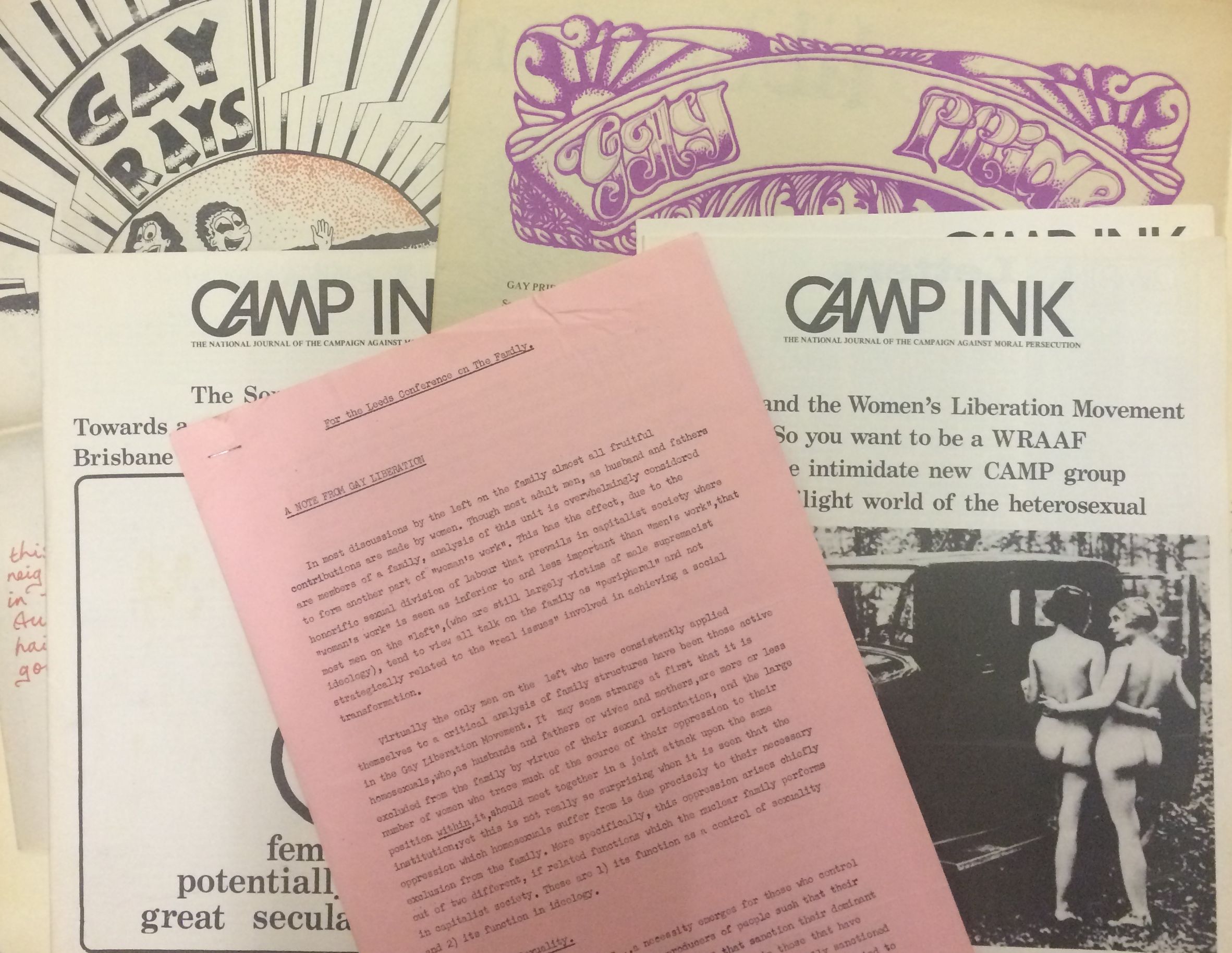

Sport searched the records of the Student Union and the Student Representative Council (SRC), material from the AUS Women’s Department and the VWLLFA, and a collection of gay liberation material that reflects the interstate links. These collections provide unique insights into the LGBTIQ histories of sexuality on campus, through the evidentiary correspondence of individual activists and the organised activities – demonstrations, conferences, publications, cultural events – of gay and lesbian groups, such as GaySoc, as well as the influence of second wave feminism.

Willett focused on the papers of Julian Phillips, who he had interviewed in 2004. Phillips had a distinguished academic career and worked for the state and federal governments in various capacities over the years. He was instrumental in the development of Victoria’s decriminalisation legislation. But we find too, evidence of his encounter with a hitherto little known organisation, the Victorian Transsexuals Coalition.

As well as the materials identified in the Archives, there is plenty of additional evidence of LGBTIQ histories by and through the University of Melbourne and its contribution to public debate and discussion and reform.

** The language used to describe same-sex desire has varied over time and at any given moment different terms are claimed and/or reclaimed with different emphasis. Historically, sodomy and inversion are known as legal and medical categories of forbidden acts; as well as a plethora of negative vernacular terms such as poofter. Camp was commonly used as a term of self-definition in Australia until gay arrived from the USA in about 1972. From the early 1970s new meanings of gay and lesbian came into the language of the liberation movement.

Queer has been in use as an umbrella label or identity of its own from the mid-1980s onwards (having been a term of abuse in the 1950s), whilst LGBTI, which stand for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Gender Diverse, Intersex has come to reflect the inclusive language of respect, integrity and human rights. LGBTI (and LGBTIQ) promotes an alliance between those who have faced historical exclusion and marginalisation. It must also be acknowledged that there are (and always will be) additional ways of describing distinct histories and experiences beyond the five letters. Sistergirls and Brotherboys for example, are affectionate words for trans people who are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, often according to geographic location.